He doesn’t

do aprons. He doesn’t do branded fry pans. He doesn’t do diffusion restaurant

lines and would never be caught dead opening in Vegas.

Actually he

almost never does TV, although he appeared once on Iron Chef, emerging like a

bear from hibernation to give Bobby Flay one of the most brutal

maulings in the show’s history (do watch the link; Flay really has no idea

what’s about to hit him).

What he does

do is quietly get on with running two-michelin starred Manresa, acclaimed by

those in the know as one of the greatest restaurants in the Bay Area, if not

the World (although unsurprisingly he only charts around #50 among the

fashionista-obsessed 50 Best Restaurant Awards. That is not a coincidence).

In short David

Kinch is the greatest chef you’ve never heard of.

Thankfully

he has done one very important piece of self-promotion.

He’s finally

written a cookbook.

The Book

Manresa: An Edible Reflection is one of

the finest cookbooks written in the last few years. Forget the soft-focus

gastro-tint from Noma.

Forget self-congratulatory ego-trips from Sat

Bains. Forget even the Upcoming Big Fat El Bulli Cookbook

(all 2,720 pages of it). If you want an example of how to capture the spirit of

a chef in three hundred pages, look no further.

Of course we

shouldn’t be that surprised. Kinch’s co-author is Christine Mulhke (pictured at right doing her scary ice-maiden look), who was last

sighted working on Eric Ripert’s On The

Line. That book is probably the best invocation of a three

star restaurant I know of – a perfect balance of cookbook and reportage. In the

world of food writers, Mulhke is out of the top draw.

The book is

a large (but not stupidly large) format volume. The publisher is Ten Speed

Press (who also did the Alinea book, the Charlie Trotter books and, er, Alan Wong’s New Wave Luau). The cover is

a detail shot of an abalone, with the ridges and whorls slightly embossed

giving a cute 3D effect. The paper is glossy and the photography is suitably

lush. In short it wouldn’t stand out from half a dozen other American/Anglo/Antipodean

cheffy volumes in the bookshop.

Okay, so far

“so what?” But where Kinch – and Muhlke – really stand out is using their three

hundred and twenty seven pages to get inside the head of the chef. That’s not

as easy as it sounds. There are a lot of cookbooks, even successful ones, which

fail miserably at this (just turn to Noma:

Time and Space in Nordic Cuisine if you want an example). Manresa, thankfully, is not like that.

Let me show

you the difference.

The Manresa Way

A tale of twelve seasons

Kinch’s food

starts with the land – unavoidably so because of his unique partnership with

Love Apple Farms. This 22 acre farm, located twelve miles from the restaurant

has only one customer – Manresa. Kitchen and farm exist in a symbiotic

relationship, with the farm planting nine months ahead and the restaurant

planning menus nine months ahead so “Ultimately, we’ll both be ready on the

same afternoon, when it goes from raised bed to plate in a matter of hours.”

For Manresa

the restaurant is as much on the farm as it is the kitchen. Kinch calls Love

Apple his “culinary laboratory”, the secret weapon which allows him to

experiment and innovate. This closeness gives his food a remarkable sensitivity

to ingredients. For Manresa there aren’t just four seasons to cook with, there

are twelve.

This is

brought out in Manresa’s signature dish called simply Into The Vegetable Garden… (p73). This is basically a riff on

Michel Bras famous Gargouillou – a

melange of individually prepared vegetables, root shoot and leaf, raw cooked

and pureed, 120 components in all each painstakingly arranged on the plate. The

concept itself isn’t new but only a restaurant with Manresa’s sensitivity can

make it the climax of the tasting menu (you know, the spot on a degustation

between the langoustine-wrapped turbot and the first pre-dessert which is

normally occupied by a foie-gras stuffed beef fillet with a truffled

demi-glace).

The pleasure principle, and California v2.0

|

| Foie Gras and Cumin Caramel. Vegans with nut allergies look away now. |

Note that

Kinch is clear that this is not a “farm to table” restaurant. The difference is

that he is not driven by politics or the need to make some sort of “more

locavore-than-thou” statement (there are plenty of recipes for foie gras

despite the state-wide bad, most notably a gorgeous foie gras-cumin crème

caramel on p116). All he cares about is producing the best damn food possible. Love

Apple gives him is complete control over the vegetables he uses in the

restaurant: What is grown, how much is grown and how good it tastes. As he

admits later in the book, “I am a hedonist. I am into the pleasure principle…

I’m not into the politics of food.”

What Kinch

does represent is the second evolution of Californian cuisine. Along with

Daniel Patterson at Coi he is at the vanguard of a generation which is moving

on from the “tyranny

of Chez Panisse”, most famously mocked by David Chang’s “figs

on a plate” jibe. Whereas Alice Waters' model revolved around respecting

the best ingredients by doing as little to it as possible, now they are trying

to play with their food more, because they feel they owe it to the ingredient.

The difference is subtle but on the plate it’s as clear as daylight.

A good

example of this is a dish called Elemental

Oyster (p134). It looks like a simple oyster on the half shell, but each

component has been carefully treated to amplify their natural flavours. The

oyster is cooked sous-vide still clamped in its shell so it poaches in its own

juices. What seems to be the natural juices is actually a cold maceration of

konbu and laiture de mer, slightly

thickened with a seaweed extract.

This is the new New California cuisine on a plate. He doesn't just present the ingredient "as is", but he doesn't torture it with hydrocolloids in a centrifuge to turn it into something it is not. Rather he applies all the tools and techniques of classical and modernist cuisine to simply make it taste more of itself.

The Evolution of a Chef

Standing on the shoulders of giants

One thing

Kinch does well is acknowledge the debt he owes to his mentors. The most

obvious is Alain Passard – who has a similar approach taking the “less-travelled

road” of one restaurant, a vegetable patch and a literary output which

constitutes “a children’s cookbook, a graphic novel, and a vegetable cookbook

featuring his own collages.” (check out Bobby Flay’s Amazon

page if you want to know what the alternative looks like). Homage is most

obviously rendered in the recipe he presents for Passard’s maple infused Arpege Egg (p52), a constant on the

Manresa menu. Also don’t miss Passard’s slightly unorthodox omelette technique

(p54) – a new way to make a very old dish.

|

| Patrick Bateman would kill to get a reservation... :-p |

The other

great inspiration is Barry Wine, the free-thinking genius behind New York

landmark The Quilted

Giraffe. This restaurant symbolised

all that was terrible and beautiful about 1980s excess (it even gets

name-checked in American Psycho). The

most famous dish were the signature Begger’s Purses, filled with Beluga caviar

and served on silver pedestals. Kinch includes his version, filled with

albacore and lightly smoked vegetables on p58. More important it opened his

eyes to Japanese (or at least Wine’s pantagruelian take on it), a sensibility

which runs through Manresa to this day.

There are

other mentions too (Kinch is nothing if not well travelled). Marc Meneau’s

famous Cromsequis of Foie Gras are

referenced with the Sweet Corn Croquettes (p114). And we have already mentioned

the influence wielded by Michel Bras’ Gargouillou.

Lessons in simplicity

Kinch is

well aware of how he adapted from other chefs, and developed. To him the

lifetime of a chef has three stages: At first you imitate which, copying from

the chefs you work with or idolise. Then you start to assimilate, putting

together ideas you have gathered and then moving ahead. But it is only in the

third and final stage that a chef finds their own voice and truly begins to

innovate.

|

| Duck with Walnut Wine: An exercise in simplicity |

When a chef

gets to this stage they actually end up cooking the simplest food they have

ever cooked because they have confidence in their technique and their style and

feel no need to hide behind unnecessary complexity. It’s at this stage that

they have developed their own independent style. When chefs get to this stage

you can look at a plate of their food and, even without being told, know it was

by Achatz, or Ducasse, or Redzepi. Or by Kinch.

Personally I

find this take refreshing in a world where chefs seem to be finding fame and

acclaim at an ever younger age. They think that, just because they’ve done a

stage at Alinea or the Fat Duck they are ready to take on the world. Luke

Thomas makes headlines simply

for being young. Hot openings like Restaurant Story or the Clove Club are

praised to the nines (take my word for it – neither of them are worth the

trip). It is, as Kinch says, “chefs trying to impress other chefs”.

David Kinch

is the antidote to all of that. To him cookery is a craft, not a get-rich-quick

scheme. The food he cooks is uniquely his own. But there are no short-cuts to

getting there. As he says in this Google Talk (8:17):

"Nowadays people are attracted to the industry because they feel that it’s incredibly glamorous. Now I can tell you I’m 52 years old and I still work til one thirty am in the morning. There’s nothing glamorous about that. I work weekends. I work nights. I work holidays. I work when you all have time to go out and eat at nice restaurants. That’s what we do."

(By the way,

if you listen to the rest of the talk you’ll also find he’s no fan of vegans

with nut allergies. But that’s a different story.)

The Food

Of abalone and pigs feet

Of course

where this all comes together is on the plate. And as a cookbook this contains

a number of remarkable recipes.

The most

outstanding are a breath-taking series of shellfish recipes in a chapter called

“The Pacific as a Muse”. Particularly noteworthy are the abalone recipes –

(Kinch is one of the few Western chefs to regularly work with this challenging

delicacy). First he serves it braised, with a delicate local milk pannacotta

and an abalone jelly (p155). Then he presents a bold Catalan-inspired pairing

with pigs trotters and milk skin (a riotous celebration of texture p158). More

classically he sautees it meuniere with

a persillade, but one made not with

parsley but seaweed (p152). These are dishes of the highest order – innovative

but with classical echoes; complex in conception but simple in execution.

The

desserts, scattered throughout the book, stand out because they often feature

vegetal elements – Candy Cap (mushroom) ice-cream with a Pine-Nut Pudding

(p184); wedges of beet with chocolate and sorrel ice-cream (p96). What’s more

interesting is the reason why – as he explains, Kinch isn’t trying to be

creative for its own sake. Rather it is to make the desserts blend more harmoniously

with the progression of the (vegetable-driven) tasting menu.

Another

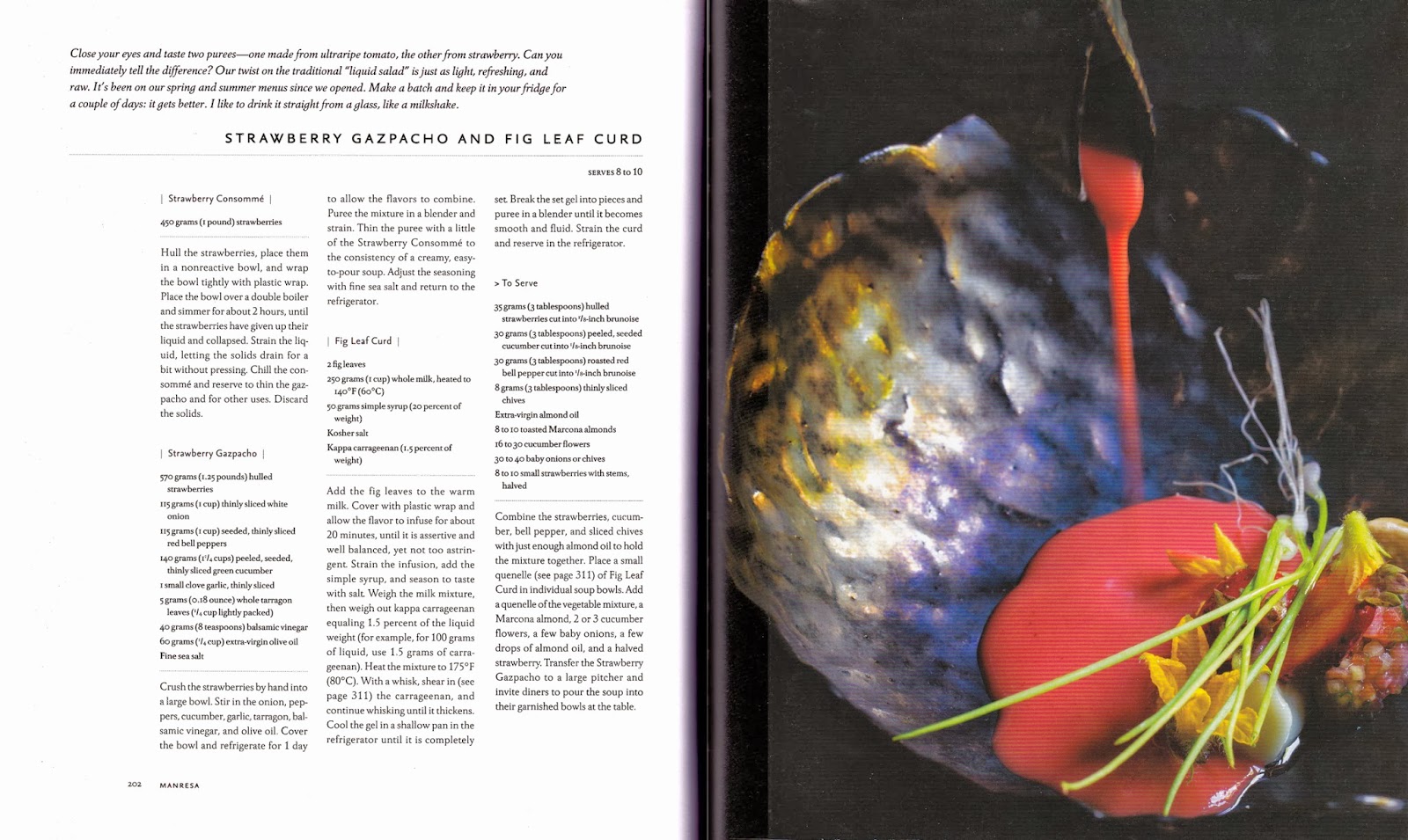

notable recipe is the Strawberry Gazpacho (p202) where refreshing strawberries

stand in for ultraripe tomato. This is one of the Manresa classics and I think

this is the first time I’ve seen the recipe in print (although Modernist Cuisine features a version,

“inspired by” Manresa). And a few pages on the Duck with Walnut Wine (p210) is

probably the most time-consuming recipes ever published in a cookbook – you need

to begin preparing the sauce 9 months before service dish (start now and you

might be able to plate up by Christmas!).

As simple as 1, 2, 3

Many of

these dishes can seem quite disorientating at first, but Kinch also provides a

really good chapter (“Building a Dish 1, 2, 3”) explaining how he comes up with

new dishes. The process is surprising simply

- First take a single ingredient. A juicy Sun Jewel Melon perhaps.

- Then find something that goes with it – it could be something that complements it (meat + potatoes). It could be something that contrasts or surprises. In this case some onions, sautéed in homemade butter and pureed with the melon

- Then add a third element – a bridge that ties the two together. This could be an unexpected ingredient, a modern technique, or even a juxtaposed texture. In this case some soft tofu laced with almond to round out the texture, and picked mackerel and chanterelles to add some acidity.

- Finally finish the dish with something dynamic – by this is means something about the dish that changes between the plate being set down and eaten. In this case the melon soup, poured tableside onto a salad of melon, mackerel and tofu.

The result

is a dish that is “balanced, complex, alive”. Sounds nuts. Somehow it works.

|

| Melon, tofu, onion. Who knew? |

Of course

it’s not that easy. It’s one thing to say “add something that contrasts” or

“find an element that ties this all together”, it’s another thing to have the

smarts to figure out what. But as a template this is a really good guide to

building a dish because it encourages you to strip the dish back to two or

three key contrasts. In my experience the number one failing of haute cuisine

chefs is to try too much as once. But for Kinch a dish is complete “not when

you can’t add anything else to it, but when you can’t take anything away.”

“He’s never going to be the one to figure out how to make hot ice cream.”

But the most

chapter in the book is when Kinch his attitude to shock-driven modernist

cuisine and its idolisation of technology.

In

particular, he rails

against the obsession with sous-vide. If you read Thomas Keller’s Under Pressure you might come away with

the impression that it’s the most wonderfully extraordinary cooking technique

ever conceived. David Kinch begs to differ. To him it’s a confidence trick. It

allows you to give cheaper cuts the same luxurious texture as scallops, racks

of veal or filet mignon, but in the process it destroys the textural integrity

of the ingredient. Lamb to him should have a bit of chew – it shouldn’t be

rendered soft, mushy and indistinguishable from the next water-bathed,

aroma-free protein:

“Softness and richness are no longer the definition of luxury. Instead, roasting celebrates meat’s inherent characteristics. Texture is at the fore: a slight chew is not a flaw but a facet to relish… Most important, the meat will retain its unique characteristics, whether veal, beef, lamb, chicken, venison or pork-something you don’t get with sous vide. Roasts tastes of what they are, making the choice of quality ingredients paramount-the true fundamental of good cooking.”

|

| Roast lamb. Sous-vide not required (don't tell Thomas Keller!) |

Another

example is the Pacojet, the industrial-strength micro-grinder which allows you

to turn any frozen block of anything into an instant ice-cream. To Kinch what

comes out of a Pacojet isn’t ice-cream. There’s no hit of rich cream and eggs.

Instead stabilisers like egg white power and dextrose are used which produce a

weird ice-cream which doesn’t taste and doesn’t melt.

To be clear

he isn’t against new technology per se. As we’ve already seen sous vide is used

to gently poach the Elemental Oyster in its juices. Pacojets are used at Manresa to make perfect

fruit sorbets or intensely flavoured herb oils. Xanthan gum is used to stablise

an emulsion of bone marrow and vegetable broth. He actually can’t shut up about

one piece of kitchen tech – his controlled-steam combi oven which lets his

program five cycle of roasting without doing a thing.

What he

hates though is fetishising technology for its own sake; turning it into an end

in itself rather than a means to an end. This is, by far, the most personal

part of the book. While everyone else ran amok with anti-griddles and thermomixes,

Kinch was ploughing his furrow (quite literally) with Love Apple and cooking

the best damn vegetables he could find in the best way he could. And the

criticism hurt. As he says:

“I felt like the voice in the wilderness, like people were saying, “Oh, look at David, growing his beets. He’s never going to be the one to figure out how to make hot ice cream.” To keep up, I experimented with all of the new technologies (or at least the ones I could afford). But I realized that the food didn’t taste good. I hated the textures. Why puree a carrot and then rethicken it with a chemical developed for industrial cooking? Sure it has an interesting texture, but it’s not the texture of a carrot, with all of its beautiful imperfections.”

Of course

now that El Bulli has faded into history it is precisely Manresa’s style of food

that has come to the fore. The restaurants which reap acclaim are places like

Noma in Denmark or L’Enclume in England, which take best of innovative

techniques, but blend them with an ineffable sense of time and place.

David Kinch

was doing that ten years ago.

Why You Should Read This Book

To wrap up,

I think there are three reasons why this is one of the finest, and most

important cookbooks to be written in recent years.

The first is

that this is a portrait of a great (and criminally under-appreciated) chef at

the prime of his powers. If you haven’t heard of David Kinch, I hope you have

now.

The second

is that it’s a masterclass in how to write a chef-driven cookbook. If you want

an object lesson in how to capture the spirit of a chef in three hundred pages,

then look no further. Ms Muhlke has done a superb job.

The third is

that this is a book packed with eternal lessons and insights are applicable to any chef. There will always a new food

fad to follow – this book warns us not to get carried away. There will always

be the temptation to add one more shaving of truffle/foie-gras/cube of crispy

belly pork to a dish – this book reminds us why less is more. Basic principles

about balance, restraint and respect for ingredients never go out of fashion.

And hopefully neither should this book.

|

| Raw Milk Pannacotta with Abalone and an Abalone-Dashi Gelee, cunningly disguised as a Damien Hirst painting |